About Me: My MS Story

My name is Joseph. In 1989, I was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. Since then, my MSer story has traveled many roads. Today, I will share the story of some of my adventures. I want to thank each of you for being here. Whenever we can come together to hear and discuss MS, I believe each of us receives energy to continue the adventure.Almost every story has a hero. My story has many. I was born in a small town in central Nebraska. We lived on the old family homestead farm without indoor plumbing or running water; three years later, when we moved to the big house, my mother told my dad she wanted an indoor toilet and water in the house. I can still see dad’s solution: a 50-gallon drum on the roof with a hose piping water from the well and electric cord attached to the stock tank heater keeping the drum’s water from freezing. By the time I was seven, I had three sisters and a brother, and we left the farm and moved to Denver.

Life with MS is like farming; praying each year that the crops don’t fail, yet knowing it’s going to happen sooner or later.

I remember my grandfather, who was one of my first heroes, telling me, “Joseph, I had a great life. Farming is hard. We struggled through the Depression. We have a great family. I started with my dad’s horse to plow fields. We bought land, tractors, and cars. We replaced oil lamps with light bulbs. We went from listening to the radio to watching television. I got to see a man walk on the moon!” Just as he was a farmer, he planted that memory in me. Personally, when I am older and my daughter is grown, maybe I will have a grandchild who I can tell, “I had a great life. I received the cure for multiple sclerosis!”

In 1968 at 18, I enlisted in the Marine Corps, which began my career working on computer-based Tactical Data Systems. I loved the technology, and I was never bored because there was always something to learn. In 45 years of working with computers, I experienced many changes first hand. The early computer programs were modified by re-wiring circuits, then machine-level switches, hole punch cards, monitors, mainframes, PC, PDA, cell, and so many other great inventions that changed our lives. MS cut that journey short.

Everyone with MS remembers their first relapse and the scared feelings after the diagnosis—“You have MS.” For me, those words came in 1989, while I was living in New York. When I was still single, after a long business trip to Japan, I was happy to be home, but also very tired. I was going down to the basement where I kept my office, and I slipped and rolled down the stairs. I lay there for 30 hours, thinking I’d broken my back, and then somehow found the strength to get up to drive myself to the emergency room. To this day, I have no idea why I didn’t call an ambulance. I’ve since learned that it’s okay to ask for help.

While I was in the hospital, the doctor told me X-rays showed a lesion on my spine at the back of my neck that looked like cancer. I was still in pain and the doctor’s words didn’t register. Meanwhile, my left hand was numb, and my arm was curled to my chest, frozen, unable to move. The doctors recommended surgery, saying the paralysis would kill me. Tests done the night before showed the lesion was shrinking and they decided not to operate. After days of testing and no clear diagnosis, incredibly, I was sent home under the care of my neurologist.

Three months later, I was stumbling and dragging my left foot. An MRI showed new scarring in the brain and my neurologist confirmed the diagnosis — multiple sclerosis. When I was first diagnosed, some people would shun me, not come into my office, walk out of meetings, or not shake my hand. I remember well those first days of being shunned. I didn’t blame them. At the time, truthfully, I didn’t know any better myself. MS is something to fear, but it is also something to understand.

Every MSer I have talked to has experienced some denial. My father showed me the courage and my mother cured my denial. One day while shopping for new shoes the numbness in my fingers made it difficult to tie the laces. Mom saw me struggling and noticed a clerk some feet away. In a clear, distinct voice said, “My son has MS, he needs help getting these shoes on.” Mom did not know it. But, my mother's love cured my denial with a few simple words.

In 1993, I began taking a disease-modifying drug to help control my disease by reducing the frequency of relapses. But by 1994, I was no longer able to work. On December 8, 1994, the doctor told me I had no choice but to retire or be confined to a wheelchair. As I was walking out the door, I had to hold on to the wall to stop me from falling. I was in shock. I cursed, “Damn it MS! You stole my career. You stole my life.” The walk to my car took forever. January 1, 1995, was not a happy New Year.

The next month, I met Debra, the woman who would become my wife. She refused to give up on me, and two years later, we were married. From the moment we met, she became my hero. I also say, she became my “Happy Heart.” I went from age 46 to 16—I would leave love notes on her car and sign them with a heart that had a smiley face inside. One day, she asked me what that was and I said, “Well, that’s my happy heart.”

My wife and I had been married for seven years, and my daughter was about five. At that time, I had numbness throughout my left side, and I used a cane in my right hand to help me walk. One day, my wife said, “Joseph, you don’t hold my hand anymore while we’re walking.” I started analyzing what she said, and I answered as an engineer, “Well, I don’t get any charge out of it.” She was hurt, and said, “I can’t believe you just said that to me.” I was surprised, too. Several months later we went to the Can-Do program at the Jimmie Heuga Center in Vail. We were listening to a lecture, not specifically on this topic, but we both had a revelation and realized a truth about MS numbness. One of the reasons for holding hands is that it feels good. Because my hand was numb, the emotional mental impulse to reach out and hold her hand got lost because of the MS. I realized it was numbness and had nothing to do with my love for my wife. We’ve worked around it…sometimes we’ll be walking and she’ll bump me and I know what that means. It elevates my awareness.

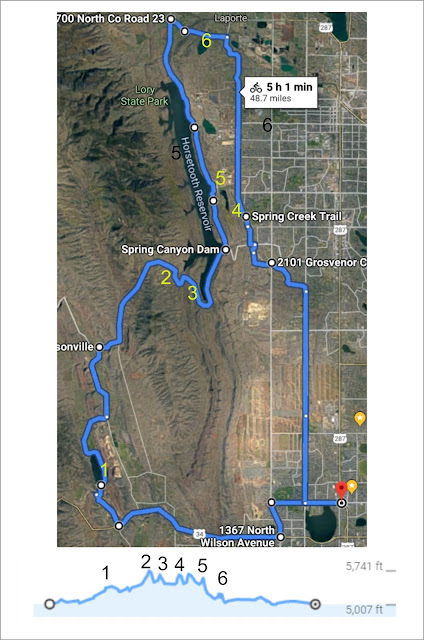

After 19 years of living with MS, my physical condition had become very stressful. I was putting on weight. Walking was fearful. After my first relapse, I walked almost everywhere with a cane. By 2008, at times, a second cane was close at hand. The situation was worsening. My excuse was MS. My daughter was getting older and my wife was taking on more responsibility. I started to change my thinking, creating a desire to overcome my lack of mobility. What followed were days, then months, and then years of personal training. I have biked five MS 150s, and two 400 mile multi-day treks, and broken both my arms.

In 2013, I started to lose the feeling in my right foot, making it difficult to slip my feet into the bike pedals. My normal way of getting on the bicycle was to lay it down, stand on my “MS” leg, and swing my good leg over. And then stand the bike up. But this relapse made it impossible for me to do that, and that was my second worse day with MS. All that training, all that work, all those perfect miles: Gone.

After two weeks, with treatment, I noticed gradual improvement; however, the damage was done by that relapse still kept me from cycling. I still look at my bikes. I look out the picture window, look at the mountains, and watch great riding days pass, determined to someday ride again.

Our journey with MS is mapped by relapses and remissions. With the modern treatments for relapses, the personal challenge is to stay in remission. Each day of remission is a chapter in a hero's journey. I’ve learned that one of the hardest things to overcome is myself; but I’ve also come to realize that I, too, am a hero on a journey. Every person with MS lives their own hero’s journey. The day you hear the words, “You have MS” the story began. Along the way, we meet mentors, support partners, treatments, remissions, and the disease. Because we adapt, the journey continues. MS is just an excuse for an adventure.

For me, the word “hero” stands for “Helping Everyone Respect Others.” Remembering how I was once shunned, I educate others that MS may be something to be afraid of—but it’s also something to understand. You can be your own hero by being proactive, discover, learn and know all your options for your MSer life. I’m grateful to my wife and my daughter, and to all the heroes I’ve met along the way. And, each of you—you are all my hero, too.